Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Refugees and Asylum Seekers-A Somewhat Challenging Australian Experience

*Corresponding author: Ingrid Muenstermann, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University of South Australia, Australia

Received: August 20, 2019; Published: August 26, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.04.000844

Abbreviations

ABS: Australian Bureau of Statistics; RAILS: Refugee and Immigration Legal Service Inc; RCoA: Refugee Council of Australia; UNHCR: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Introduction

This article is written by a social scientist, a sociologist, who is concerned about Australia’s current treatment of refugees and asylum seekers. The previously welcoming attitude of politicians, policy makers and people has changed considerably and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Services ‘keep Australia safe’: no maritime arrivals will be processed in Australia nor will they ever can settle in Australia. Asylum seekers arriving by boat at Australia’s shores have been transferred to Manus Island or Nauru. These so called ‘processing centres’ are closed, however, during a recent Australian Senate Estimates Committee hearing, the deputy commissioner of the Department of Home Affairs, Mandy Newton, provided figures for asylum seekers on Nauru: there were 652 asylum seekers on the island as of October 22. Of those, 541 (or 83%) have been granted refugee status; 88 people (13%) were still subject to the ‘refugee status determination’ process; and 23 were considered ‘failed asylum seekers’ [1]. This is a challenging issue because these people, young men, have been there for more between five and seven years. Although the detention centers are now officially closed and the ‘detainees’ have open access to the outside, these young men are in a state of fear and uncertainty and their health, especially mental health, is of concern.

In the following, information is provided about Australia’s changing policies and attitudes in relation to asylum seekers and refugees who arrive ‘unauthorized’ and ‘by boat’. Australia has declared itself a multicultural society in 1972. The 2016 Census data reveals that of 24,641,662 people almost 25% of the population is born in another country. Looking at the 2016 Census [2], two thirds (67%) of the Australian population are born in Australia. Further data of the ABS [2] demonstrates that almost half (49%) of Australians has either been born overseas (are first generation Australians) or have one or both parents born overseas (representing the second generation of Australians). Of the 6,163,667 people born overseas, nearly one in five (18%) have arrived since the start of 2012. The 2016 Australian Census [2] also points out that while England and New Zealand are the next most common countries of birth after Australia, the proportion of people born in China and India has increased since 2011 (from 6.0% to 8.3%, and from 5.6% to 7.4%, respectively). The same Census shows that there are more than 300 separately identified languages spoken in Australian homes. More than one-fifth (21%) of Australians speak a language other than English at home. After English, the next most common languages spoken at home are Mandarin, Arabic, Cantonese, and Vietnamese.

Australia has welcomed people from more than 180 countries since its European settlement in 1788, and as an immigration country can present itself as a relatively harmonious society. Australia’s immigration policies have changed during the last 65 years from focussing on attracting migrants for the purpose of increasing Australia’s population to a focus on attracting workers and temporary (skilled) migrants in order to meet the skilled labour needs of the economy [3]. With changes in policies and its Border Protection Bill in 2001, it has become harder to enter Australia without a visa and to become a citizen. Australian citizenship is a person’s status in relation to Australia and carries with its certain responsibilities and privileges. The Australian Citizenship Act 1948 determines who holds Australian citizenship. A person may acquire Australian citizenship by birth, adoption, descent, resumption or grant of Australian citizenship (naturalization) [3].

As a signatory of the Refugee Convention Australia has a responsibility of protecting asylum seekers and refugees, but there are signs that its previous welcoming attitude towards people in need of protection has become more cautious during the last 30 or so years. This will be briefly discussed. The change in attitude towards people in need can partly be related to a change in labor market requirements (manual labor has been shifted to developing countries, the car industry is declining) but also to a fear of terrorism since 9/11. This article looks at Australia’s past and present immigration policies, at the development of settlement programs, different streams of immigration and at different types of visas and the protection and entitlements embedded in these visas. A challenging aspect of Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers (Tampa affair and Pacific Solution) will be discussed briefly. Overall it is concluded that Australia as a multicultural society has so far functioned well, that life is relatively peaceful, but that Australian politicians need a different approach to settle asylum seekers and refugees.

The objective of this article is to determine policies regarding refugees and strategies for settlement of humanitarian entrants. This study should be a benchmark to compare the settlement of refugees and humanitarian entrants in other countries.

The methodology is a literature review, using official Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and Census data, publications of the Refugee Council of Australia (RCoA), of the Refugee and Immigration Legal Service (RAILS), and of other suitable literature.

Defining would be Settlers in the Australian Content

Migrants: The ABS [3] defines migrants as people who are born overseas but whose usual residence is Australia; for instance, if people have been (or are expected to be) residing in Australia for a period of 12 months or more.

Refugees: A refugee is a person who was subject to persecution in their home country and who is in need of resettlement [3]. Most applicants who are considered under this category are identified by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and referred by the UNHCR to Australia [3].

Asylum seekers: People who have sought protection as a refugee, but whose claim for refugee status has not yet been assessed [4,5]. Under international law, a person is a ‘refugee’ as soon as s/he meets the definition of refugee, whether their claim has been assessed or not.

Humanitarian entrants: As far as could be determined, refugees, asylum seekers, and people belonging to the group of refugee family reunion are being categorized as humanitarian entrants. They are holders of a qualifying humanitarian visa, such as that of refugee (subclass 200), In-country special humanitarian (subclass 201), Global humanitarian (special humanitarian program) (subclass 202), Emergency rescue (subclass 203), and Woman at risk (subclass 204) [6-8]. For further discussion, please see below.

Background of Australia’s settlement of refugees and asylum seekers

Looking at the European history of Australia, it has granted assisted passages to people who wanted to reside in this country since 1831 [9]. Assisted passages stopped officially in 1980. Australia has supported approximately 750,000 refugees since Federation in 1901 [10]. In 1952 Australia became one of the 145 countries to sign the Refugee Convention [11], which defined the term ‘refugee’ and outlined their rights. The UNHCR (n.d.) defines refugees as “people who have fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country”.

The RCoA [4,5] provides a more specific definition, namely that “a refugee is any person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his/her nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself/herself of the protection of that country”. An interesting point here is that Australia’s program to settle German refugees’ dates to 1839: Lutherans, trying to escape worship restrictions in Prussia, settled in Hahndorf and Klemzig, South Australia. But according to RCoA [10], there were people from several other European countries who left because of religious and political persecution to find refuge in Australia.

After Federation in 1901, “refugees were allowed to settle as unassisted migrants, as long as they met the restrictions imposed by the Immigration (Restriction) Act, the basis for the White Australia Policy” [10]. Between 1933 and 1939, 7,000 Jewish people, fleeing Nazi Germany, also found refuge in Australia. During World War II, settlement programs were suspended, but in 1947, Australia arranged with the newly formed International Refugee Organization to settle displaced persons from camps in Europe: 170,000 people from Poland, Yugoslavia, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Ukraine, Czechoslovakia and Hungary entered Australia over the next seven years. The Australian arrangements with the International Refugee Organization and with European countries to admit refugees and later on to embark on large immigrant intakes had two main reasons: Australia’s population in 1945 was 7,430,197 and there was a need to improve the capacity to defend itself [12], ‘populate or perish’ was the catch cry. At that point in time, the ‘yellow peril’ was greatly feared. But Australia also wanted to move from primary to secondary industry, for which it needed more people and a wider knowledge base.

The following is an overview of Australia’s contribution to absorb people from countries in crises after 1955: [10]. These people were admitted and provided with the opportunity to settle apart from those in refugee camps in Europe:

In 1956 The Hungarian Revolution;

In 1968 Warshaw Pact countries invaded Czechoslovakia;

In 1972 Uganda’s President Idi Amin expelled Asian settlers;

In 1973 Military coups deposed the Allende Government in Chile;

In 1974 Turkish invasion of Northern Cyprus;

In 1975 War in East Timor, evacuees were brought to Darwin;

1975 Fall of the South Vietnamese Government in Saigon. Vietnamese refugees fled into nearby countries, triggering international interference. Australia pledged to help and between 1975 and 1995, has resettled more than 100,000 Vietnamese refugees from different Asian countries. In 1975 there were also 2,000 Vietnamese people who arrived by boat illegally and without being invited. They are the so called ‘boat people’.

Development of settlement institutions and programs

Up until the 1970s, there were no specific strategies in place to help refugees or migrants settle and to acculturate in Australia. At migrant receiving camps people would be accommodated, provided with necessities to live and, most importantly, provided with advice regarding employment. The political and economic circumstances of that time need to be remembered: Europe was in turmoil with millions of people being displaced and Australia having a shortage of workers. That many new settlers were only able to speak very basic English or did not know the language at all, was not important, as manual Laboure’s, which Australia needed to move from primary to secondary industry, they were able to survive and to contribute to Australian society in a positive way. But the world-wide refugee crisis increased and forced Australia to be pragmatic. In 1977 Michael Mackellar, the then Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, developed a national refugee policy, entitled the Galbally Report [10]. This report looked at ways of helping newcomers to settle in Australia, of maintaining their cultures, and of ensuring they had the same rights and access to services as other Australians [13]. Overall there was a strong emphasis on increased involvement of voluntary agencies.

The following is a summary of agencies of strategies that were created by the Australian government:

According to the [10], in 1977, Migrant Resource Centers were established in capital cities; in 1979 a loan scheme was created to help refugees to buy their own home; 1979 also saw the further development of Adult Migrant and Settlement Education Programs, and, most importantly, a Community Refugee Settlement Scheme was established in 1981, which involved community groups to provide “newly-arrived refugees with on-arrival accommodation, social support and assistance of finding employment”. In 1981, a Special Humanitarian Program was also created to provide settlement options to people who had suffered serious discrimination or human rights abuses, had fled their home country and had close ties with Australia. Because of growing awareness of the psychological impact of persecution, in 1988, the first torture and trauma services were established. In 1989, a special visa category within the refugee program was developed to make possible priority settlement for refugee women at risk and their children. In 1991, a Special Assistance Category visa was created because of catastrophes countries, allowing people in vulnerable circumstances and with connections to Australia, to resettle. This program was phased out in 1997 because it had become a family reunion program (which is a special category within the Australian refugee settlement scheme).

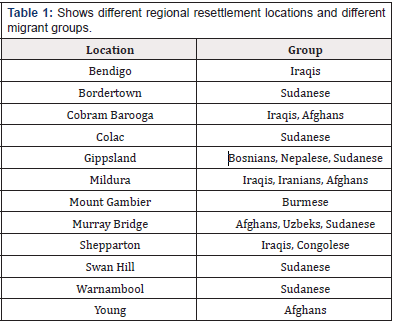

The most important change to the settlement services involved settling people in rural and regional areas, matching them with people of the same ethnic background. According to the [10], changes of the regional distribution of refugees and of service provisions were necessary because the cohort of refugees has changed considerably: while people of mainly European decent had made up the majority of refugees in the past, from the 1990s on, people from Africa and the Middle East make up the vast majority [14,10]. Hugo argues that these people, despite being costly to settle, make a valuable contribution to Australian society, to the three ‘Ps’, population, participation and production: these refugees “are meeting some important and significant labor shortages in Australia’s regional areas”, despite “the difficulties that have been experienced by humanitarian settlers in these locations” [14]. Here is a summary of refugees and humanitarian arrivals, cited in the [10] (Table 1).

According to the best estimates available, 2009-10 was the year in which Australia, since becoming an independent nation, passed the 750,000 mark in its intake of refugees and humanitarian entrants. From Federation in 1901 until 1948, no official statistics were kept of refugee settlement. However, research published by the Australian Parliamentary Library estimated that Australia received 20,000 refugees in this period. From July 1948 to June 1977, Australia received 269,266 assisted humanitarian arrivals, as well as another 33,000 unassisted humanitarian arrivals, according to DIAC estimates. Since the modern Refugee and Humanitarian Program began in 1977, Australia has received 392,538 offshore refugee and humanitarian entrants and has issued 42,714 onshore protection visas.

Who fits the bill? Australia’s streams of migrants and different visa categories.

Australia’s migration programs have three different streams, business, skilled and family migration [14,15,4,5]. There is also a special eligibility migration stream. Looking at the different visa categories (see below), one can see how very complex the system is. First, it needs to be mentioned that all visa applicants need to undergo health checks and fulfil certain character requirements; applicants for all permanent visas are required to sign an Australian Values Statement [15].

Business migration: Of importance is that Australia is very keen to attract business migrants, i.e. businesspeople investing substantial amounts of money can obtain a business skills visa if they have established skills and a genuine commitment to owning and managing a business in Australia [16].

Skilled migration: Individuals are being assessed according to a skilled migrant category, a point system based on age, work experience, qualifications, and knowledge of the English language [13].

Family migration: This stream aims to reunite immediate and extended family members with their eligible Australian relatives. Applicants wishing to migrate under this scheme must be sponsored by a close family relative who is an Australian [13].

Special eligibility migrants: Former citizens wanting to return to Australia must fulfil health and character requirements (required for all visas) [13].

No specific ‘refugee stream’ could be identified, however, the latest figures according to Phillips [12] demonstrate Australia’s intake of migrants: During 2015-2016, Australia accepted 57,400 people under the family reunion scheme, 128,550 people under the skilled migration program (including business migrants),under the special eligibility scheme, 308 people were admitted, and 3,512 children were resettled in Australia. The figure of people who were processed under the humanitarian program was 17,555.

Any person residing in a foreign country needs a visa; this determines their status in relation to their ability to reside in that country. In general, there are permanent and temporary visas and it is usually easier for a migrant than for a refugee to obtain a permanent visa or permanent residence status. A permanent resident is legally defined as a person who was born overseas and has obtained permanent Australian resident status prior to or after arrival [16]. According to the RCoA [4,5], the difference between migrants and refugees is based on, and clarified by, international law, with different treaties and bodies being responsible for migrants and for refugees. The distinction is reflected in Australia’s policies, which include both a Migration Program and a Refugee and Humanitarian Program. The RCoA [4,5] raises the interesting point that labelling refugees as being ‘migrants’, ignores the protection they need.

Humanitarian programs have been developed for refugees and other people with specific humanitarian needs. This program has two functions: the offshore assessment and resettlement component, and the onshore protection / asylum component [17]. This program is of major interest; it determines different kinds of visas. It is important to mention that after arrival in Australia, all temporary visa holders are entitled to Australia’s Status Resolution Support Services. This service provides support to people who are living in the community on temporary visas, or who are in community detention while their application for refugee status is assessed. It constitutes a regular payment to help with basic living costs [18].

Here is a brief overview of different visas and their basic entitlements. We are starting with onshore assessments and protection:

• Permanent Protection Visas (subclass 866): are visas granted to persons who enter Australia unlawfully, but are then found to be refugees based on the guidelines of the United Nations 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol of the Status of Refugees, or to be at real risk of suffering significant harm in their home country [19]. These people are usually confined to and assessed in various Australian detention centers.

Bridging Visa (BVA) (subclass 010): According to the Australian Government [17], this temporary visa allows applicants to stay in Australia after their current visa ceases and while their substantive visa application is being processed.

Offshore Refugee and Humanitarian Visas (subclasses 200- 219) are visas granted to persons outside Australia who are subject to persecution or substantial discrimination in their home country. The most important visas for offshore refugees are the following categories:

• Refugee (visa subclass 200) (Visa Help Australia, n.d.): This is a permanent residence visa. It allows people to stay in Australia indefinitely, work and study, access Medicare (Australia’s public health care system), and social security payments, attend English classes, apply for Australian citizenship after four years in Australia, and propose family members for permanent residence.

• In‐Country Special Humanitarian (visa subclass 201): This visa is for individuals who are living in their home country and are subject to persecution in their home country, face immediate threats to their lives or to their personal security, but have not been able to leave that country to seek refuge elsewhere [6,7]. This visa provides individuals with the right to live, work and study in Australia indefinitely, access Medicare, access social security benefits, attend English language classes, apply for citizenship, and propose family members for permanent residence.

• Emergency Rescue (visa subclass 203): This visa gives priority processing for people who are in immediate danger [6,7]. This is a permanent residence visa. It allows individuals to stay, work and study in Australia indefinitely, access Medicare, access certain social security payments, attend English language classes, apply for Australian citizenship after four years of living in Australia, and propose family members for permanent residence.

• Women at Risk (visa subclass 204): This visa provides women who do not have the protection of a partner or a relative and are in danger of victimization [6,7,19]. According to ISA Migration [20], this visa is applicable for females who want to live, study and work in Australia. It is a permanent visa. Applicants must have a recommendation by the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees to the Australian Government. This recommendation makes their application considered for relocation to Australia. These individuals can access Medicare and social security benefits, can attend English language classes, can apply for citizenship after four years in Australia, and can sponsor family members for permanent residence.

• Global Special Humanitarian Visa (subclass 202): According to Visa Help Australia [11], applicants must live outside Australia when applying for the visa. They must also be outside Australia when a visa is granted. Their application must be proposed by a person or organization in Australia. The individuals must experience substantial discrimination which amounts to a gross violation of human rights in their home country. Holders are entitled to stay, work and study indefinitely in Australia, access Medicare, access certain social security payments, attend English language classes, apply for Australian citizenship after four years, and can propose family members for permanent residence. If they want to travel outside Australia, they need to get a travel document. After five years, they will need a Resident Return Visa to re-enter Australia.

Demonstrating the even greater complexity of visa applications are the Safe Haven Enterprise Visa (SHEV) and the Temporary Protection Visa (TPV).

• Safe Haven Enterprise Visa (SHEV) (Subclass 790): According to the Australian Government [21], this visa is for people who arrive in Australia illegally and apply for protection. A SHEV allows people to stay in Australia work and / or study, access Medicare, receive some social security payments, and access English language classes. According to the RCoA [4,5], a SHEV is current for five years and the holder can apply for a permanent migration visa after that time (but not a permanent protection visa). Of advantage is when SHEV holders during their stay in Australia are financially self-sufficient and / or work or study in a regional area. When applying for permanent residence, these people must also meet the criteria of other permanent visas (for instance, as the husband or wife of an Australian citizen). This visa does not allow the holder to travel to the country from which s/he has been granted protection. It does also not allow the holder to sponsor family members for a visa.

• Temporary Protection Visa (TPV) (subclass 785): According to the Australian Government [22], this visa is for individuals who arrive in Australia without a valid visa and apply for protection on the grounds of race, religion, nationality, political opinion and/or membership of a particular social group. Immigration Australia [14] points out that applicants must show cause that because of leaving their home country they would face arbitrary deprivation of life, the death penalty, torture, or cruel, degrading and inhuman treatment. The TPV allows individuals to stay and work in Australia for three years, access Medicare, and receive some social security payments. According to the RCoA [4,5], TPV holder cannot apply for permanent residency, however, prior to the expiry of that visa, another TPV or SHEV can be lodged. The claim for protection will be re-assessed.

As can be seen, different visas are available for different circumstances; none of the categories includes asylum seekers and refugees on Nauru. The difficulty is to be accepted under Australian law and on Australian soil as being someone in need of protection. It is also important that claims for protection are (in theory) assessed as quickly as possible in order to avoid stressful situations, especially when held in custody in detention centers in Australia or offshore. Business and skilled migrants are preferred; Australian policies also look favorably at refugees and humanitarian entrants who have worked and studied in regional areas.

Social Services Benefits (Centrelink) of Visa Holders

Various entitlements of holders of different visas have been outlined above. Here is a summary of benefits or services that can be accessed once a visa has been granted. The Asylum Seeker Status Resolution Support Services will stop, and Centrelink Special Benefits can be claimed if readily available funds are less than $5000. Bank statements must be provided to Centrelink who will assess the situation every 13 weeks. Visa holders can work but must inform Centrelink about their income. They are entitled to Medicare, job seeker assistance and, depending on the type of visa, individuals can access short-term counselling for torture and trauma. According to RAILS [9,23], visa holders are also entitled to family tax benefit, single income family supplement, double orphan pension, parental leave pay, dad and partner pay, child care benefit, school kids bonus, child dental benefit, care fee assistance, stillborn baby payment and to the low income health care card. As mentioned before, an advantage in relation to claim permanent residence, i.e. a permanent migration visa, is when a refugee or humanitarian entrant is/was financially independent (does not/ did not rely on social security benefits) and has worked or studied in a regional area.

Changing Australian Policies and A Shameful Aspect of it

Australia has experienced three waves of asylum seekers who arrived by boat. Unfortunately, negative public opinions, prompted by the creation of fear by far-right politicians and the supporting press, provoked Australia’s politicians to introduce mandatory detention and the Pacific Solution [24] for people arriving ‘unauthorized’ (without a visa), being called ‘illegal immigrants’, and are labelled ‘queue jumpers’, ‘unlawful non-citizens’, and ‘illegal maritime arrivals’ [25]. Between 1976 and 1981, 2059 Vietnamese boat people arrived. These people were welcomed. The arrival of 27 Indochinese asylum seekers in November 1989 started the second wave. During the following nine years, boats arrived at the rate of about 300 people per annum – mostly from Cambodia, Vietnam and southern China. In 1999, the third wave of asylum seekers, predominantly from the Middle East, began to arrive; often in larger numbers than previously and usually with the assistance of ‘people smugglers’ [24].

Apart from ‘illegal immigrants’, who officially will never be able to settle in Australia, the country accepts a fluctuating number of refugees and humanitarian entrants. RCoA [26-29] reports an increase from 13,750 to 20,000 in 2012-13, then back to 13,750, followed by an increase to 16,250 in 2017-18, to be further increased to 18,750 in 2018-19. 2015 saw a one-off intake of 12,000 people to be resettled in Australia because of the crises in Syria and Iraq. As these figures imply, immigration is a hotly discussed topic in parliament; the whole issue is highly politicized. According to RCoA [26-29], between 2012 and 2017, 51,637 people arrived by boat seeking asylum and at least 862 deaths have occurred at sea. Both, the Coalition (Liberal Party and National Party) and the Labor Party use the fact that many people drowned as reason for not accepting and assessing unauthorized arrivals by sea.

The Pacific Solution was legalized in 2001 and is discussed by the RCoA [2-4] in the following. It has been the most controversial policy in relation to the handling of asylum seekers ever since. Based on the Pacific Solution asylum seekers arriving by boat were being transported to and detained in Nauru and on Manus Island. These Australian offshore detention centres (politicians call them offshore immigration processing centres) were created in 2001, suspended in 2008, but reopened in 2012 because of large numbers of so-called ‘maritime arrivals of asylum seekers. The Manus Regional Processing Centre closed officially in October 2017; people were transferred to different facilities on Manus. The Nauru Regional Processing Centre closed officially in March 2019 but, as the Australian Senate Inquiry established, 652 asylum seekers are still on the island with no hope to be resettled in Australia but are also unable to return to their home countries. They have been on the island between five and seven years and there is a general understanding that their health, especially mental health, is deteriorating.

Let us dig a little deeper into the history of the Pacific Solution. Since the second wave (1989) of boat arrivals entered Australian shores, the Australian public has been concerned. Prior to 1992 so called unauthorized boat arrivals (asylum seekers) were held in detention under the Migration Act 1958 on a discretionary basis. This changed in 1992. The Labor Government legislated the Migration Amendment Act, starting mandatory detention of all citizens who do not hold a valid visa. A further change occurred in 2001 when the Liberal Government introduced legislative changes allowing some of Australia’s territory to be excised from the migration zone in order to discourage non-citizens from arriving unlawfully in Australia by boat. As discussed by Phillips and Spinks [24], under the Pacific Solution so called unauthorized arrivals at excised places were transferred to offshore processing centers in Nauru and on Manus Island. They are detained while their asylum claims are being processed. These claims are not processed under Australian law and the claimants have no access to legal assistance or judicial review.

Very important here is the statement by Janet Phillips, who finds that Asylum seekers who arrive by boat are subject to the same assessment criteria as all other asylum applicants. Past figures show that between 70 and 100 per cent of asylum seekers arriving by boat at different times have been found to be refugees and granted protection either in Australia or in another country [25]. Despite these people being genuine refugees, it seems that only a few have been resettled, mainly in countries other than Australia. Some resettlements may have taken place in Australia, however, the process is not transparent, media access to the offshore processing centers is denied, medical and other staff who work at the centers are not permitted to talk about their experiences, and members of the Coalition and of the Labor Party emphasize continuously that people detained in Nauru and on Manus Island will not be settled in Australia.

A large part of the Australian population has been appalled by these measures [30-33] and the pressure on politicians is mounting to resettle these people as soon as possible. “The Pacific Solution was widely criticized by refugee advocacy and human rights groups as being contrary to international refugee law, unjustifiably expensive to implement, and psychologically damaging for detainees” [24]. In February 2019, the Refugee Medical Evacuation Bill was passed by the Australian Parliament after very intense negotiations. This does mean “innocent people languishing on Manus Island and Nauru are able to access the healthcare they need, when they need it” [15]. Up until now, not a medical professional but an administrator decided whether a detainee needed medical attention. Twelve deaths have occurred in the detention centers, some could have been avoided had the refugees received adequate medical care. Now treatment will take place in Australia on Christmas Island, but the asylum seekers will have to return to Nauru or Manus Island.

A trigger of the Pacific Solution was the so-called Tampa affair, an incidence which many Australians find challenging to accept and shameful. In August 2001 the Coalition government under the leadership of Prime Minister John Howard refused permission for the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa to enter Australian waters. MV Tampa had rescued 433 asylum seekers and five crew members from a fishing vessel in distress [34]. When the captain of the Tampa refused to turn around and did enter Australian waters, the Prime Minister ordered the ship be boarded by Australian Special Forces (SASR) to prevent it from closer approaching Christmas Island. In doing this, he confirmed Australian sovereignty and determined who will enter and reside in Australia.

The Norwegian government condemned the Australian government; it had failed to meet its obligations to distressed mariners under international law and complained to the United Nations. According to International law, survivors of a shipwreck are to be taken to the closest suitable port for medical treatment. The closest suitable port was 12 hours to Merak, Indonesia. Christmas Island, Australia, was six or seven hours closer [35], however, according to Shaltbolt (cited in Wikipedia) it did not have the ability to receive large shopping freighters. The Australian troops instructed the captain of the Tampa to move the ship back into international waters, he refused, claiming that ship was unsafe to sail until the asylum seekers had been offloaded. Norway refused to admit the asylum seekers, so did Indonesia; in the end, the asylum seekers were loaded onto a Royal Australian Navy vessel and transported to Nauru.

The inhumane situation becomes clear when looking at the assessment of the captain of the Tampa: I have seen most of what there is to see in this profession, but what I experienced on this trip is the worst. When we asked for food and medicine for the refugees, the Australians sent commando troops on board. This created a very high tension among the refugees. After an hour of checking the refugees, the troops agreed to give medical assistance to some of them… The soldiers obviously didn’t like their mission [10].

The Social and Economic Contributions of Humanitarian Entrants to Australian Society

Apart from moral issues which the detention of people in Nauru and Manus Island raise, some thought is provided here in relation to the overall contribution of asylum seekers and refugees. Graeme Hugo looks critically at different nationality groups of humanitarian entrants and their contributions to Australia society. He asserts that “the marked increase in capacity over time of humanitarian entrants and their subsequent generations … is very significant”; he particularly mentions the “resourcefulness, hard work and determination to improve their lives and the life of their children” [17]. Interestingly, comparing different migrant visa categories, Hugo [17] finds that an important aspect of humanitarian entrants is that they, compared to other migrant groups, tend to spend their entire lives and raise their children in Australia. But he does acknowledge that there are barriers confronting this group when entering the workforce; the knowledge of English is of great importance and not speaking the language does present difficulties.

Unemployment rates are higher and workforce participation rates are lower. However, this changes for the second generation: “at least half of the nationality groups have a higher level of participation [in the workforce] than those born in Australia, with ten of the nationality groups having lower level of unemployment rates than the Australia-born” [17]. This author also finds that humanitarian arrivals value the education of their children: a higher proportion (of those aged 15-24) attend educational institutions than other migrant categories and the Australia-born population. [17] concludes that the difficulties experienced by the first generation dissipate for the second generation. Does this demonstrate acculturation of Australian culture, convergence towards Australian values or is it something else? How can the success of second-generation migrants be understood? Muenstermann (1997) talked about this issue.

The success of the second generation is based on sacrifices of the first generation, on their efforts to push their children to achieve high levels of education. This, of course, reduces the barriers over time. The more specific economic contribution of humanitarian entrants is related to their sense of becoming independent, of establishing their own businesses (more so than other migrant groups), to engage disproportionally in the workforce in regional areas, and to initiate trade between their home countries and Australia [17]. Assessing the social capital of humanitarian arrivals [17], community contributions, close networking within their own ethnic groups and volunteering could be established.

New refugee communities have a strong connection to their immediate communities and promote these. But there is also engagement with the broader community, they volunteer at official organizations, which is a means of gaining confidence, learning about new communities, and of feeling empowered. Different groups take different length of time to engage with the broader community; it is affected by cultural norms, time spent in refugee camps, and the availability of leadership within the community. The overall finding of Hugo [17] is that the economic and social contributions of humanitarian entrants are substantial even though they experience greater difficulty in adjusting to life in Australia than other migrant groups.

Conclusion

This literature review has looked at Australian refugee and asylum seeker policies and demonstrated that Australia, despite being a signatory to the United Nations 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol on Refugees, is not always acting humanely when it comes to assist people in need of protection. One only needs to look at the labelling of asylum seekers or refugees, such as ‘illegal immigrants’, ‘illegal maritime arrivals’, ‘queue jumpers’, ‘unlawful non-citizens’ to realize that people are victimized and humiliated. During the last 30 years Australia has applied increasingly stricter laws (enforced by Border Protection and border patrols), one of them being that no asylum seeker arriving by boat will be settled in Australia. Since 2001, boats, if discovered by border patrols, have be turned back (to Indonesia) or if a vessel should make it to Australian shores, people have been detained in offshore detention centers in Nauru or on Manus Island.

These centers have officially been closed, but there are still more than 600 people (young men) awaiting resettlement. In February 2019 (13.02.2019) the Australian parliament talked about people who have been in these detention centers for about 5 to 7 years. Medical care (up until 13.02.2019) was determined necessary or not necessary by administrators and not by medical professionals, the media had/has no access to the centers, and employees were / are not allowed to talk about their experiences. Overall transparency is lacking, and human rights violations have occurred. Looking at Australia’s different visa categories and the entitlement of the holders, there can be no doubt that on paper human rights have been addressed in relation to privileges and responsibilities of refugees and humanitarian entrants. The difficulty is to understand Australia’s treatment of, and policies in relation to, asylum seekers who arrive by boat. As Phillips [25] points out, 70% to 100% of ‘illegal maritime arrivals’ have been assessed as being genuine refugees.

Therefore, it can be argued that they will face deprivation of life, the death penalty, torture, or cruel, degrading and inhuman treatment if they return to their home countries. Reports of investigative journalism [8,36-39] find that the treatment in the offshore detention centers is unquestionably inhumane; many individuals have developed physical and mental illnesses, children as young as 12 self-harmed; and twelve deaths have occurred. In order to prevent further tragedy, it is time that people in the offshore detention centers to be resettled. There must be a better solution to protect Australian borders!

While this article cannot comment on the contribution’s asylum seekers/refugees in Australian offshore detention centers, mention is made here of Behrouz Boochani, a young Kurdish-Iranian writer, journalist, scholar, cultural advocate and filmmaker, ‘writing from Manus Prison’ [40-17].

His book No Friend but the Mountains won the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award 2019. It captures the enormous courage, resilience and hope of detainees on Manus Island; but it also implies the degrading, dehumanizing treatment of asylum seekers by those in the corridors of Australian power. The unprejudiced study by Hugo [17] is of some consolation; the author argues that humanitarian entrants contributed significantly to Australian society, that they influenced the three ‘Ps’, population, participation and production. There can be no doubt that people detained right now on Manus Island and in Nauru would make a positive contribution to Australian society [45-50].

References

- RMIT University Melbourne (ABC) (2018) Fact Check.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] (2017) 2016 Census: Multicultural. Media Release.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] (2016) Migrant Data Matrices. Cat No. 3415.0.

- Refugee Council of Australia [RCoA] (2016) Temporary protection.

- Refugee Council of Australia [RCoA] (2016) Who is a refugee? Who is an asylum seeker?

- Social Security Guide (2019) Permanent Refugee and Humanitarian Visas. Guides to Social Policy Law. Canberra: Australian Government.

- Social Security Guide (2019) Qualification for CrP-Humanitarian Entrant Summary. Guides to Social Policy Law, Canberra: Australian Government.

- Tlozek, Erik (2019) The Promised Land. Australian Broadcasting Corporation program, Foreign Correspondence.

- Refugee and Immigration Legal Sercice Inc (RAILS) (2018) SHEV abd TPV visas. Centrelink Benefits.

- Rinnan, Captain of MV Tampa, Tampa Affair.

- Visa Help Australia (n.d.) Australian Department of Home Affairs.

- Phillips Janet (2017) Migration to Australia: A quick Guide to the Statistics. p. 1-7.

- Ding H, Schmidt TW, Pino T, Güthe F, Maier JP (2003) Towards bulk behavior of long hydrogenated carbon chains? Phys Chem Chem Phys 5: 4772.

- Cataldo F, Keheyan Y (2006) Polyynes: Simple synthesis in solution through the glaser reaction. In: Cataldo F (ed) Polyynes: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. CRC Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, pp: 493- 498

- Liu M, Artyukhov VI, Lee H, Xu F, Yakobson BI (2013) Carbyne from First Principles: Chain of C Atoms, a Nanorod or a Nanorope. ACS Nano,

- Bylaska EJ, Weare JH, Kawai R (1998) Development of Bond-Length Alternation in Very Large Carbon Rings: LDA Pseudopotential Results. Phys Rev B 58: R7488–R7491.

- Saito M, Okamoto Y (1999) Second Order Jahn–Teller Effect on Carbon 4N+2 Member Ring Clusters. Phys. Rev. B 60: 8939–8942.

- Jahn HA, Teller E (1937) Stability of Polyatomic Molecules in Degenerate Electronic States. I. Orbital Degeneracy. Proc R Soc London A 161: 220- 235.

- Rubin Y, Kahr M et al (1991) The higher oxides of carbon C8nO2n (n = 3-5): synthesis, characterization, and x-ray crystal structure. Formation of cyclo[n]carbon ions Cn+ (n = 18, 24), Cn- (n = 18, 24, 30), and higher carbon ions including C60+ in laser desorption Fourier transform mass spectrometric experiments. J Am Chem Soc 113: 495.

- Handschuh H, Ganteför G, Kessler B, bechthold PS, Eberhardt W (1995) Stable Configurations of Carbon Clusters: Chains, Rings, and Fullerenes. Phys Rev Lett 74: 1095-1098.

- Wakabayashi T et al (1997) Photoelectron spectroscopy of Cn produced from laser ablated dehydroannulene derivatives having carbon ring size of n = 12, 16, 18, 20, and 24 J Chem Phys 107: 4783.

- Martin JML, El-Yazal J, François JP (1995) Structure and vibrational spectra of carbon clusters C n ( n = 2-10, 12, 14, 16, 18) using density functional theory including exact exchange contributions. Chem Phys Lett 242: 570-579.

- Atkins P, Friedman R (2005) Molecular Quantum Mechanics. 4th edn. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Fukui K, Yonezawa T, Nagata C, Shingu H (1954) Molecular orbital theory of orientation in aromatic, heteroaromatic, and other conjugated molecules. J Chem Phys 22: 1433-1442.

- Lewis G (1923) Valence and the Structure of Atoms and Molecule. The Chemical Catalog Company, inc.

- Chigo E, Torres A, Hernández H (2014) Studies of graphene–chitosan interactions and analysis of the bioadsorption of glucose and cholesterol. Appl Nanosci 4: 911–918.

- Kadokawa JI (2014) Preparation of Chitin-Based Nano-Fibrous and Composite Materials Using Ionic Liquids. In: Han-Chan C, Hua-Chia C, Thomas S (ed) Physical Chemistry of Macromolecules: Macro to Nanoscales, CRC Press, Apple Academic Press, New Jersey, pp 367-384

- Rodriguez A, Chigo E, Hernandez H, Flores A (2013) Adsorption of chitosan on BN nanotubes: A DFT investigation. Appl Surf Sci 268: 259– 264.

- Delley B (1995) DMol, a standard tool for density functional calculations; review and advances. In: Seminario JM, Politzer P (eds) Modern density functional theory: a tool for chemistry. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp: 221-254.

- Auckenthaler T, Blum V, Bungartz HJ, Huckle T, Johanni R, et al. (2011) Parallel solution of partial symmetric eigenvalue problems from electronic structure calculations. Parallel Computing 37: 783.

- Delley B (1990) An all‐electron numerical method for solving the local density functional for polyatomic molecules. J Chem Phys 92: 508.

- Delley B (2000) From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J Chem Phys 113: 7756-7764.

- Perdew JP, Wang Y (1986) Accurate and simple density functional for the electronic xchange energy: Generalized gradient approximation. Phys Rev B 33: 8800-8802.

- Perdew JP (1991) Generalized gradient approximations for exchange and correlation: A look backward and forward. Physica B 172:1-6.

- Perdew JP, Wang Y (1992) Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys Rev B 45:13244-13249.

- Estrada E (2002) Physicochemical Interpretation of Molecular Connectivity Indices. J Phys Chem A 106: 9085-9091.

- Pacheco JH, Zaragoza IP, Bravo A (2017) Interaction of small carbon molecules and zinc dichloride: DFT study. Rev Mex Fís 63: 97–110.

- Atkins P, De Paula J (2010) Physical Chemistry. Freeman and Company, New York.

- Guibal E, Milot C, Tobin J (1998) Metal-anion sorption by chitosan beads: equilibrium and kinetic studies. Ind Eng Chem Res 37:1454-1463.

- Isidro FJ, Pacheco JH, Desales LA (2017) Hydrogen Storage on lithium decorated zeolite templated carbon, DFT study. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy.

- Hernández-Benitez D, Pacheco-Sánchez JH (2018) Optimization of Chitosan+ Activated Carbon Nanocomposite. DFT Srudy. Arc Org Inorg Chem Sci 3(5): 436.

- Sakurai K, Maegawa T, Takahashi T (2000) Glass transition temperature of chitosan and miscibility of chitosan/poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) blends. Polymer 41: 7051–7056.

- Suvachittanont W, Kurashima Y, Esumi H, Tsuda M (1996) Formation of thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (thioproline), an effective nitrite-trapping agent in human body, in Parkia speciosa seeds and other edible leguminous seeds in Thailand. Food Chem 55(4): 359-363.

- Tunsaringkarn T, Suwansaksri J, Rungsiyothin A, Palasuwan A (2014) Cell proliferation activities in vitro model of Thai mimosaceous extracts. J Chem Pharm Res 6(1): 507-511.

- Tsuda M, Kurashima Y (1991) Nitrite-trapping Capacity of Thioproline in The Human Body. IARC Sci Publ 105: 123-128.

- Nakatogawa H and Ohsumi Y (2008) Starved cells eat ribosomes. Nat Cell Biol 10: 505- 507.

- Uyub AM, Nwachukwu IN, Azlan AA and Fariza SS (2010) In vitro antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of selected medicinal plant extracts from Penang island Malaysia on metronidazole resistant Helicobacter pylori and some pathogenic bacteria. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 8: 95-106.

- Sakunpak A, Panichayupakaranant P (2012) Antibacterial activity of Thai edible plants against gastrointestinal pathogenic bacteria and isolation of a new broad spectrum antibacterial polyisoprenylated benzophenone, chamuangone. Food Chem 130(4): 826-831.

- Gmelin R, Susilo R, Fenwick GR (1981) Cyclic polysulphides from Parkia speciosa. Phytochemistry 20(11): 2521-2523.

- Musa N, Wei LS, Seng CT, Wee W, Leong LK (2008) Potential of Edible Plants as Remedies of Systemic Bacterial Disease Infection in Cultured Fish. Glob J Pharmacol 2(2): 31-36.

- Randhir R, Ms YL, Shetty K (2004) Phenolics, their antioxidant and antimicrobial activity in dark germinated fenugreek sprouts in response to peptide and phytochemical elicitors. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 13(4): 295-307.

- Wonghirundecha S, Sumpavapol P (2012)Antibacterial Activity of Selected Plant By-products Against Food- borne Pathogenic Bacteria. Int Conf Nutr Food Sci 39(1): 116-20.

- Thitilertdecha N, Teerawutgulrag A, Rakariyatham N (2008) Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Nephelium lappaceum L. extracts. LWT - Food Sci Technol 41(10): 2029-2035.

- Suklampoo L, Thawai C, Weethong R, Champathong W, Wongwongsee W (2014) Antimicrobial Activities of Crude Extracts from Pomelo Peel of Khao-nahm-peung and Khao-paen Varieties. KMITL Sci Technol J 12(1).

- Mokbel MS, Hashinaga F (2009) Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Banana (Musa, AAA cv. Cavendish) Fruits Peel. Am J Biochem Biotechnol1( 3): 125-131.

- Fatimah I (2016) Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using extract of Parkia speciosa Hassk pods assisted by microwave irradiation. J Adv Res 7(6): 961-969.

- Mustafa NH, Ugusman A, Jalil J, Kamisah Y (2018) Anti-inflammatory property of Parkia speciosa empty pod extract in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Appl Pharm Sci 8(1): 152-158.

- Gui JS, Jalil J, Jubri Z, Kamisah Y (2019) Parkia speciosa empty pod extract exerts anti-inflammatory properties by modulating NFκB and MAPK pathways in cardiomyocytes exposed to tumor necrosis factor-α. Cytotechnology 71(1): 79-89.

- Kamisah Y, Zuhair JSF, Juliana AH, Jaarin K (2017) Parkia speciosa empty pod prevents hypertension and cardiac damage in rats given N(G)-nitro- L-arginine methyl ester. Biomed Pharmacother 96(8): 291-298.

- Karunaweera N, Raju R, Gyengesi E (2015) Plant polyphenols as inhibitors of NF-κB induced cytokine production- a potential anti-inflammatory treatment for Alzheimer’s disease? Front Mol Neurosci 8(6): 1-5.

- Sorriento D, Santulli G, Fusco A, Anastasio A, Trimarco B, et al. (2010) Intracardiac injection of AdGRK5-NT reduces left ventricular hypertrophy by inhibiting NF-κB-Dependent hypertrophic gene expression. Hypertension 56(4) 696-704.

- Huang GJ, Huang SS, Deng JS (2012) Anti-inflammatory activities of inotilone from Phellinus linteus through the inhibition of MMP-9, NF-κB, and MAPK activation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 7(5).

- Martin ED, Felice De Nicola G, Marber MS (2012) New therapeutic targets in cardiology: P38 alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase for ischemic heart disease. Circulation 126(3): 357-368.

- Galindo P, Gonzalez-Manzano S, Zarzuelo MJ, Gomez-Guzman M, Quintela AM, et al. (2012) Different cardiovascular protective effects of quercetin administered orally or intraperitoneally in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Funct 3(6): 643-650.

- Huang WY, Fu L, Li CY, Xu LP, Zhang LX, et al. (2017) Quercetin, Hyperin, and Chlorogenic Acid Improve Endothelial Function by Antioxidant, Antiinflammatory, and ACE Inhibitory Effects. J Food Sci 82(5): 1239-1246.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.