Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Positive Role of Green Tea as An Anti-Cancer Biomedical Source in Iran Northern

*Corresponding author: Ebrahim Alinia-Ahandani, Department of Biochemistry, Payame Noor University, PO BOX 19395-3697 Tehran, I.R. Iran

Received: August 08, 2019;Published: September 03, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.05.000870

Abstract

Tea, green gold, is the second famous beverages in the world. Tea was not grown in Iran until the late 1800’s, after an Iranian diplomat, by the name of Kashef Al Saltaneh, smuggled back from India over 3,000 samplings to plant in Iran. In general, green tea contains about 30% (w/w) of catechins in the dry leaves. The major catechins are epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) epigallocatechin (EGC), (-)-epicatechin (EC), and (-)-epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), which comprise more than 60% of the total catechins. Other green tea conclusion are the flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol, and rutin), caffeine, phenolic acids, the green tea specific amino acid theanine, and flavour compounds such as (Z)-3 hexenols and its esters. Increased consumption of green tea had a potentially preventive effect on breast cancer in a Japanese population. combined green tea composition with other bioactive dietary components may be an appropriate way to improve its effects in cancer prevention. Several studies have shown that the fat-lowering effect of green tea and EGCG is mediated by SREBPs.in this short review around some effects of green tea on cancer prevention and positive effects on body. We hope use and focus on this herb fundamentally in Iran northern as a center of this green gold in healthcare.

Keywords: Tea; Cancer; Breast; Iran; SREBP

Introduction

Green tea, Camellia sinensis (L.) family Theaceae. Tea, beside water, is the second famous beverages in the world. Green tea is mainly consumed in Japan and China and Iran, whereas black tea is primarily consumed in Western countries, India, and other parts of the world [1,2,3,4]. Green tea was first brought to Japan, more than 1000 years ago, from China as a form of medicine. Tea was not grown in Iran until the late 1800’s, after an Iranian diplomat, by the name of Kashef Al Saltaneh, smuggled back from India over 3,000 samplings to plant in Iran. (Given that the English stole from the Chinese to grow tea in India, I guess it is fitting to have their tea stolen as well.) His story is an interesting one, as Kashef was educated in Europe and serving in India in the Iranian consulate. He decided to smuggle back the samplings to plant in his hometown of Lahijan in the northern Gilan region of Iran (on the Caspian Sea), [1,6,7,8] which had the perfect terroir for tea. He succeeded in smuggling as his diplomatic position prevented the British military from searching his suitcases and trunks. After six years of trying, he got his product to market and Iranian tea traditions have not been the same. [9,10,11]. Tea plantations are still in full production today in the regions of Gilan producing tea in the traditional orthodox fashion. Demand for tea far outstrips the supply in the country, so tea is still imported from Africa, Middle East, and India. In 1211, the Japanese Zen monk Eisai published a book entitled “Kissa Youjouki” which means “promotion of health by tea”, and described that “tea is a marvelous preventive medicine to maintain people’s health and has an extraordinary power to prolong life” [9,12,13,14]. Indeed, recent scientific evidence has shown that green tea is beneficial for health-promotion [6,13,15-18].

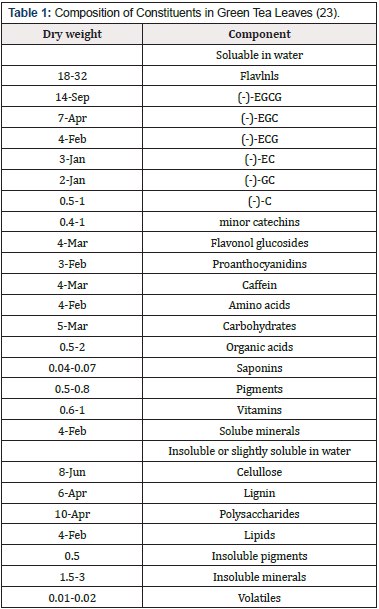

As the various production processes, teas can be included into three kinds: green tea [non-Fermented tea), black tea (fermented tea), and oolong tea (semi-fermented tea). The raw compound of all of these teas are the leaves of the tea plant Camellia synesis and its varieties. During fermentation, a series of complex chemical reactions takes place; the most important one representing the oxidation of polyphenols [19,20]. This results in the formation of teaflavins thearubigins, and other oxidized-polymerised compounds, which are responsible for the characteristic color and flavor of black tea [20-24]. In old years, green tea had a remarkable medical duty in medicine in several European Pharmacopoeias. Recently, some of hepatic attack after the use of hydroalcoholic extracts of green tea in complement of human dietss [3,4,6,16,25]. The conclusion of constituents of a green tea is highly dependent on the amount of used tea leaves, on the extraction time, and on the quality of water used for extraction. Therefore, the composition can be subject to a strong variance within a certain range (Table 1).

The traditional supplement of green tea as an infusion includes a broad spectrum of components of the drug. In general, green tea contains about 30% (w/w) of catechins in the dry leaves [26]. The major catechins are epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) epigallocatechin (EGC), [-)-epicatechin [EC), and (-)-epicatechin-3- gallate (ECG), which comprise more than 60% of the total catechins (Figure 1) [5,6,22,25,27].

Other green tea conclusion are the flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol, and rutin), caffeine, phenolic acids, the green tea specific amino acid theanine, and flavour compounds such as (Z)-3 hexenols and its esters [1,23, 26,28]. After vast description of green tea catechins are well absorbed [15,22]. Catechins are then bio transformed in the liver, and presumably already in the intestine [6,29,30], to conjugated metabolites such as glucuronidase, methylated sulfated derivatives. While EGC and EC are predominantly conjugated, EGCG is often present in the free form in human plasma [11,17,23,31]. In the colon deconjugation may happen due to tissue -glucuronidases and microflora [19,32]. After absorption the catechins are widely spread to the various tissues with concentrations presumably not exceeding the lower micromolar to nanomolar range (0.1 M) [27,31]. Other traditional indications of green tea includes: For oral use, diuresis, mild diarrhea, recovery from fatigue, and dietary supplement for weight reduction and for external use, calm for itching of skin ailment and treatment of cracks, grazes, and insect bites, etc. [1,4,6,7,15,33]. The traditional Chinese medicine has recommended this plant for headaches, body aches and pains, digestion, depression, detoxification, as an energizer and, in general, to prolong life, beneficial effects in oral diseases such as protection against dental caries, periodontal disease, and tooth loss [which may significantly affect a person’s overall health). Numerous studies have demonstrated that the aqueous extract of green tea possesses antimutagenic, antidiabetic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and hypocholesterolemia properties [2,21,25,29].

Green tea effects as anti-breast cancer

Over the three decades ago, green tea has attracted increasing attention for its health benefits, especially anti-cancer effects. As early as 1997 there was an epidemiological study showed that increased consumption of green tea had a potentially preventive effect on breast cancer in a Japanese population, especially among females drinking more than 10 cups a day. Since then, the association between green tea consumption and breast cancer risk has been extensively investigated [3,17,31,33]. Among the two studies of breast cancer recurrence, both found a non-significant reduction in recurrence among heavy green tea drinkers [> 3 cups a day). There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies [P = 0.65, I2 = 0%). This analysis suggested a marginally significant reduction of 27% in recurrence among heavy green tea drinkers [> 3 cups a day) [summary RR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.56-0.96) when compared to nondrinkers [8,14,17,26]. Among the breast cancer incidence studies, two were cohort studies and five were case-control studies. Overall, there was a statistically significant reduction of 19% among women with high green tea intake (summary RR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.75-0.88). The epidemiological studies on the association between green tea and breast cancer remain inconclusive. Remarkably, green tea may also interact with other bioactive dietary components, such as those in soy and mushroom, to affect breast cancer risk [8,14,27]. A study in Asian-American women demonstrated a statistically significant inverse association between green tea and breast cancer risk among women with low soy intake, but not among women with high soy intake [11,12,22,30]. A case-control study indicated that higher dietary intake of mushrooms decreased breast cancer risk in pre- and postmenopausal Chinese women, and an additional decreased risk of breast cancer from joint effect of mushrooms and green tea was observed. These data suggested that combined green tea composition with other bioactive dietary components may be an appropriate way to improve its effects in cancer prevention. However, additional studies are required to elucidate the potential mechanisms of action [4, 7,9,13,34]

Effects of green tea on SREBPs

SREBPs are the transcription factors which play a central role in regulation of cellular lipogenesis and lipid homeostasis [5,7,32]. Several studies have shown that the fat-lowering effect of green tea and EGCG is mediated by SREBPs [3,12, 21,29,35]. In diet-induced obese mice, dietary EGCG lowered the levels of plasma triglycerides and liver lipid [15,31]. In the epididymal white adipose tissue, EGCG decreased the mRNA levels of adipogenic genes such as SREBP- 1c, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, and fatty acid synthase. Our animal experiment showed that oral administration of a catechin-free fraction reduced plasma levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, with concomitant reduction in hepatic gene expression of SREBPs [2,4,36,11]. Thus, green tea contains lipidlowering components in addition to GTC. Several human studies have shown that green tea and EGCG have the lipid lowering effect [20,25,34]. For example, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on 56 obese, hypertensive subjects consuming a daily supplement of 1 capsule with 379 mg of GTE for 3 months, the GTE group was found to show reductions in the total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides as compared with the placebo group [1,7,10,20,28,37].

References

- Alinia-Ahandani E (2018) Medicinal plants and their usages in cancer. J Pharm Sci Res 10: 2-2.

- Feng Q, Kumagai T, Torii Y, Nakamura Y, Osawa T, et al. (2001) Anticarcinogenic antioxidants as inhibitors against intracellular oxidative stress. Free Radic Res 35 (6):779-788.

- Siegmund OH, Fraser CM (1979) Reproductive and urinary system. In: Merk Veterinary manual. published by Merck and co. Inc. Rahway, N.J. USA. Pp: 794-890.

- Mei J, Yeung SS, Kung AW (2001) High dietary phytoestrogen intake is associated with higher bone mineral density in postmenopausal women but not premenopausal.J. Clin.Entomol. metab.86(11): 5217-5221.

- Alinia-Ahandani E, Fazilati M, Alizadeh Z, Boghozian A (2018) The Introduction of Some Mushrooms as an Effective Source of Medicines in Iran Northern. Biol Med (Aligarh) 10: 451.

- Gupta RS, Sharma A (2003) Antifertility effect of Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) stem extract in male rats . Indian J Exp Biol 41(8): 885-889

- Wu CD, Wei GX (2002) Tea as a functional food for oral health. Nutrition 18(5): 443-444.

- Ahandani IA, Asadisamani M, Biranvand M (2010) The introduction of nettle. Monthly of Barzegar 1042: 43.

- Gupta S, Ahmed N, Mohan RR, Husain MM, Mukhtar H (1999) Prostat cancer chemopreventation by green tea: In vitro and in vivo inhibition of testosterone mediated induction of ornithine decarboxylase .Amer. Assoc. Cancer Res 59(9): 2115-2120.

- Shahin MR, Dehghani F, Khozani TT, Pharm ZP (2005) The effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Actinidia Chinensis on sperm count and motility, and on the blood levels of estradiol and testosterone in male rats. Arch Iranian Med 8(3):211-216.

- Alinia-Ahandani E, Boghozian A, Alizadeh Z (2019) New Approaches of Some Herbs Used for Reproductive Issues in the World: Short Review. J Gynecol Women’s Health. 16(1): 555927.

- Alinia-Ahandani E (2018) Medicinal plants effective on pregnancy, infections during pregnancy, and fetal infections. J Pharm Sci Res 10: 3-3.

- Zheng G, Sayama K, Okubo T, Junefa LR, Oguni I (2004) Anti-obesity effects of three major components of green tea, catechins, caffeine and theanine in mice. In vivo 18 (1): 55-62.

- Zhen YS (2002) Tea-Bioactivity and therapeutic potential. London: Taylor & Francis: 57-88.

- AL-Mansoor NA (1995) Effect of Ibicella lutea on biological aspects of white fly bemisia tabaci Thesis, Basra.

- Amantana A, Santana-Rios G, Butler JA, Xu MR, Whanger PD, et al. (2002) Antimutagenic activity of selenium-enriched green tea toward the heterocyclic amine 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f] quinoline. Biol Trace Elem Res86 (2):177-191 .

- Who: Protocol MD- 50 (1983) A method for the examining the effect of plant extract administration orally on the fertility of male rats (APF/IP .99/4E). World Health organization.

- Tian WX, Li LC, Wu XD, Chen CC (2004) Weight reduction by Chinese medicinal herbs may be related to inhibition of fatty acid synthase. Life Sci. 74(19): 2389-2399.

- Aura AM, O Leary KA, Williamson G, Ojala M, Bailey M, Puupponen-Pimia R, Nuutila AM, Oksman-Caldentey KM, Poutanen, K (2002) Quercetin derivatives are deconjugated and converted to hydroxyphenylacetic acids but not methylated by human fecal flora in vitro. J Agric Food Chem 50(6):1725-1730.

- Willson KC (1999) Coffee, Cocoa and Tea. New York: CABI Publishing.

- Pan TH, Jankovic J, Le WD (2003) Potential therapeutic properties of green tea polyphenols in Parkinson’s disease. Drugs Aging 20(10): 711- 721.

- Rietveld A, Wiseman S (2003) Antioxidant effects of tea: Evidence from human clinical trials. J Nutr 133(10): 3275-3284.

- Chow HH, Cai Y, Alberts DS (2001) Phase I pharmacokinetic study of tea polyphenols following single-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.10(1): 53-58.

- Varnam AH, Sutherland JP (1994) Beverages: Technology, Chemistry and Microbiology. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Costa LM, Gouveia ST, Nobrega JA (2002) Comparison of heating extraction procedures for Al, Ca, Mg and Mn in tea samples. Ann Sci 18 (3):313-318.

- Graham HN (1992) Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry. Prev. Med. 21(3): 334-350.

- Yang CS, Chen L, Lee MJ, Balentine D, Kuo M, Schantz SP (1998) Blood and urine levels of tea catechins after ingestion of different amounts of green tea by human volunteers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 7(4): 351-354.

- Yang CS (1997) Inhibition of carcinogenesis by tea Nature. 389: 134-135.

- Chantre P, Lairon D (2002) Green tea extract reduce body weight in obese adults-clinical trial. Phytomedicine 14(9): 3-8.

- Zhang MH, Luypaert J, Pierna JAF, Xu QS, Massart DL (2004) Determination of total antioxidant capacity in green tea by near-infrared spectroscopy and multivariate calibration. Talanta 62(1):25 –35.

- Lee MJ, Maliakal P, Chen L, Meng X, Bondoc FY, Prabhu S, Lambert G, Mohr S, Yang CS (2002) Pharmacokinetics of tea catechins after ingestion of green tea and (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate by 93 humans: formation of different metabolites and individual variability. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 11(10):1025-1032.

- Kroon PA, Clifford MN, Crozier A, Day AJ, Donovan JL, Manach C, Williamson G, (2004) How should we assess the effects of exposure to dietary polyphenols in vitro? Am J Clin Nutr 80(1):15-21.

- Raji Y, Salman TM, Akinsomisoye OS (2004) Reproductive function in male rats treated with methanolic extract of Alstonia boonei stem bark. Afric. J. Biomed.Res. 8:105 -111.

- Seddik M, Lucidarme D, Creusy C, Filoche B (2001) Is Exolise hepatotoxic? Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 25(8-9): 834-835.

- Cabrera C (2006) Beneficial effects of green tea-A Review. J Amer Colle Nutrition 25(2): 79-99.

- Satoh K, Sakamoto Y, Ogata A, Nagai F, Mikuriya H, Numazawa M, Yamada, Aoki N (2002) Inhibition of aromatase activity by green tea extract catechins and their endocrinological effects of oral administration in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 40(7): 925-33.

- Rietveld A, Wiseman S (2003) Antioxidant effects of tea: Evidence from human clinical trials. J Nutr 133(10): 3275-3284.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.